Midweek Musing: Fear, Control, and Perception - Seeing the Divide in America

When do we move past fear and all the other BS? What will it take?

As a Black woman, a documentarian, and someone who has spent years witnessing the intersections of power, vulnerability, and everyday life, I’ve been watching the latest news from Washington, D.C., and now, my hometown of Chicago, with a mix of curiosity and unease.

On social media, two very different fears are circulating: one, that crime is spiraling out of control and the government must intervene; the other, that government intervention itself is a threat, a sign of overreach that could spread and escalate.

Both fears are rooted in a sense of losing control, yet both are often disconnected from the realities of our recent history—crime rates are lower than they’ve been in decades, and day-to-day life has been relatively free from the kinds of authoritarian measures some imagine.

From this vantage point, the patterns of fear I see online—on both sides—reveal more about perception than reality. Watching these narratives collide, I keep asking: how do we have a conversation when perception and fear, more than evidence or shared reality, are driving the debate of what’s really happening in this country?

And what does it mean for someone like me to interrogate these fears—someone who not only innately understands that the stakes of both personal safety and government power are profoundly real, but is constantly gaslit into believing that my concerns should take a back seat to someone else’s?

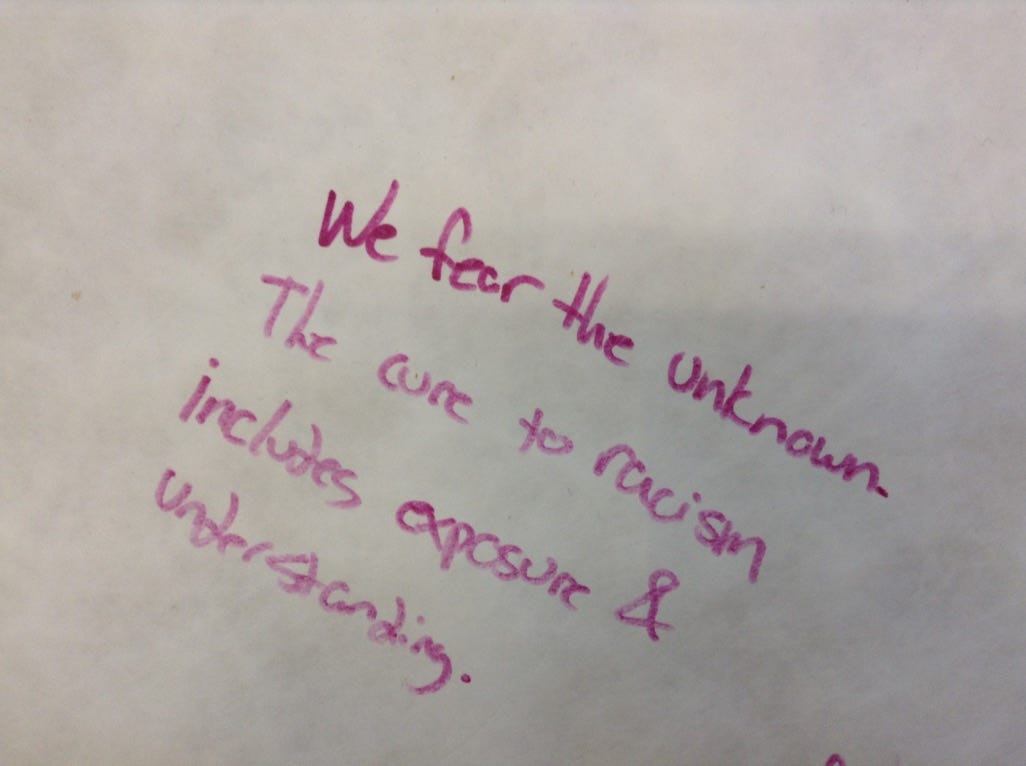

On one side, there’s a fear that crime is spreading unchecked, that society is tipping toward chaos, and that only decisive government action can restore safety and stability. For many on the right, the presence of federal forces in D.C. feels like a necessary intervention—a way to reclaim a sense of order that feels threatened. The irony is that they embrace the very chaos that they feel will mitigate the perceived threat of chaos that has been somehow orchestrated against them. Talk about a need for shadow work…

On the other side, there’s a fear that government intervention itself is the threat, that overreach could normalize the erosion of civil liberties and expand authoritarian control. For the left, any display of governmental power in the streets is less about addressing criminal behavior, but more about a signal of potential encroachment on freedoms they hold dear. I’m not saying that they’re wrong, but I’m also not saying that we are all one step away from all being chained up and locked up in camps. There are some on the left who will never have to experience this.

Both sides are operating from a sense of vulnerability, yet the objects of that vulnerability differ, and the measures they see as protecting their agency often place them in direct opposition to each other.

What’s striking is that both fears, while emotionally compelling, exist in a context where crime is lower than it has been in decades and where, for most Americans, daily life has been largely free from the kind of state intervention that sparks alarm.

These dynamics are not confined to urban crime; they appear in policies like deportation and border enforcement, where fear similarly drives government action. Under slogans like “America First” or “protecting the border,” the government asserts authority in the name of safety and stability.

Yet for those affected, these interventions represent a direct curtailing of freedom, mobility, and agency. Deportation, like federal occupation in cities, is justified through fear of economic disruption, cultural change, or lawlessness—yet it reveals the uneven ways government power is exercised and whose liberties are considered expendable.

It’s a stark reminder that “protection” often carries real consequences for marginalized communities, and that the perception of regaining control for some comes at the expense of the freedom of others.

Yet looking at these examples in context shows that, despite intense fear, crime rates have declined over decades, and everyday life has remained largely free from authoritarian intervention.

Policies like deportation and federal occupation may feel immediate and alarming, but they are part of a broader historical pattern in which fear is used to justify government action, often targeting specific communities while leaving others largely untouched. This creates a kind of “latent fear,” where the emotional resonance of potential threats outweighs the evidence of contemporary reality, and historical memory fills in gaps, amplifying anxieties about safety, stability, and agency.

Even when we talk about abstract values like safety, stability, and agency, it becomes clear that what these concepts mean differs depending on one’s perspective.

For the right, safety often means protection from chaos and disorder caused by crimes committed by Black people, often in communities that are of considerable distance from them, with government intervention seen as a necessary enforcer of stability.

For the left, safety can mean freedom from government coercion, and stability involves protecting civil liberties against the expansion of state power. But there is an unwillingness to speak truth to power, that the protection of civil liberties must extend first to those who have the appropriate mix of racial and/or cultural capital and are seen as having the most to lose. Similarly, those who have the least to lose are often times situated in communities that are of considerable distance from them; there’s little to no connection with those communities.

Some on the right also worry about government overreach, but often selectively, are blind to ways their own actions or behaviors intersect with the systems they critique. They see their actions in direct opposition to governmental intervention as justified or appealing to a higher cause.

Nevertheless, the result is that each side believes it is defending a set of values, often shared but corrupted by inverted definitions, and in practice, marred by conflict. This inversion helps explain why social media and public discourse often feel like a loop of misunderstanding, with each side talking past the other while anchored in fear rather than shared reality.

Understanding these inverted definitions requires perspective, which brings me back to my own positionality and why I am interrogating these dynamics. My questions about fear, control, and perception are not abstract—they come from a place shaped by a complicated lived reality.

As a Black woman, a documentarian, and someone who has witnessed social and political tensions firsthand, I have seen how fear is experienced differently depending on one’s position in society. These experiences allow me to recognize both the validity and the distortions in the fears circulating on all sides of the political spectrum.

I can see why some perceive crime as an urgent threat and why others view government action as overreach, and I can also observe how historical patterns and structural inequities amplify these perceptions. This positionality gives me the vantage point to ask questions that others may overlook: how much of our fear reflects reality, and how much is shaped by the narratives we inherit and the systems we navigate? Yet perspective comes with responsibility: observing fear is not the same as overriding the lived realities of those directly affected.

Even with my experience and perspective, I recognize that communities have the right to define their own experiences. In D.C., for example, residents may feel safe, and that assessment should hold weight against executive orders, distant media reports or social media narratives claiming otherwise.

This tension between observation and intrusion is what frustrates me most about online discourse, where outsiders insist they know the truth of a place without engaging with the people who actually live there. As a documentarian, I have learned to reserve judgment, to listen first, and to let those experiencing a community’s reality speak before forming conclusions.

This tension between observation and lived reality plays out in striking ways online. Recently, I observed online dialogue involving a man—a Washington, D.C. resident —who insisted that he felt safe in his neighborhood before the federal occupation. Instead of being acknowledged, he was mocked and viciously trolled by others, including the original poster. There were people who didn’t live in the city, who insisted that this man’s own assessment was wrong because it didn’t fit their narrative of imminent danger.

Moments like this highlight the absurdity of the discourse: lived experience is dismissed in favor of fear-driven assumptions, and perception becomes louder than reality. It’s a stark reminder of why listening to those directly affected is not just a courtesy, but essential to understanding what’s actually happening on the ground.

Incidents like this underscore the broader challenge: how fear, perception, and unevenly distributed control shape public discourse, often at the expense of reality. Ultimately, the challenge of fear in America is not just about crime rates or government action—it is about perception, context, and the gaps between lived experience and outside narratives. Both sides operate from fear, yet their objects of concern, definitions of safety, and visions of control often conflict, making dialogue fraught. My role, as someone positioned to observe and reflect, is not to claim authority over how others experience their communities, but to interrogate the patterns and perceptions that shape our responses to uncertainty. Perhaps the most important takeaway is a reminder to listen before judging, to distinguish perception from reality, and to recognize that control—real or imagined—is never evenly distributed.

Engaging with fear in this way does not resolve the divisions, but it opens a space for awareness, reflection, and a more measured understanding of the forces shaping our collective anxieties.